“I remember that day.”

Fewer and fewer World War II veterans in this country can say that about D-Day — June 6, 1944 — the anniversary of which we commemorate this week. While some 16 million Americans served in World War II, less than 400,000 of those servicemen now remain with us, according to the National World War II Museum.

Yet on that day in June 1944, nearly 160,000 American, British, and Canadian forces landed on five beaches on the heavily guarded coast of France’s Normandy region.

It was one of the largest amphibious military assaults ever.

The key victory there for the Allies against Nazi Germany, which had been occupying Western Europe, became a turning point in World War II.

For many veterans of that war, the successful invasion and decisive victory encompassed far more than a single day, of course — the war consumed their young lives and turned them from boys to men in a mere blink.

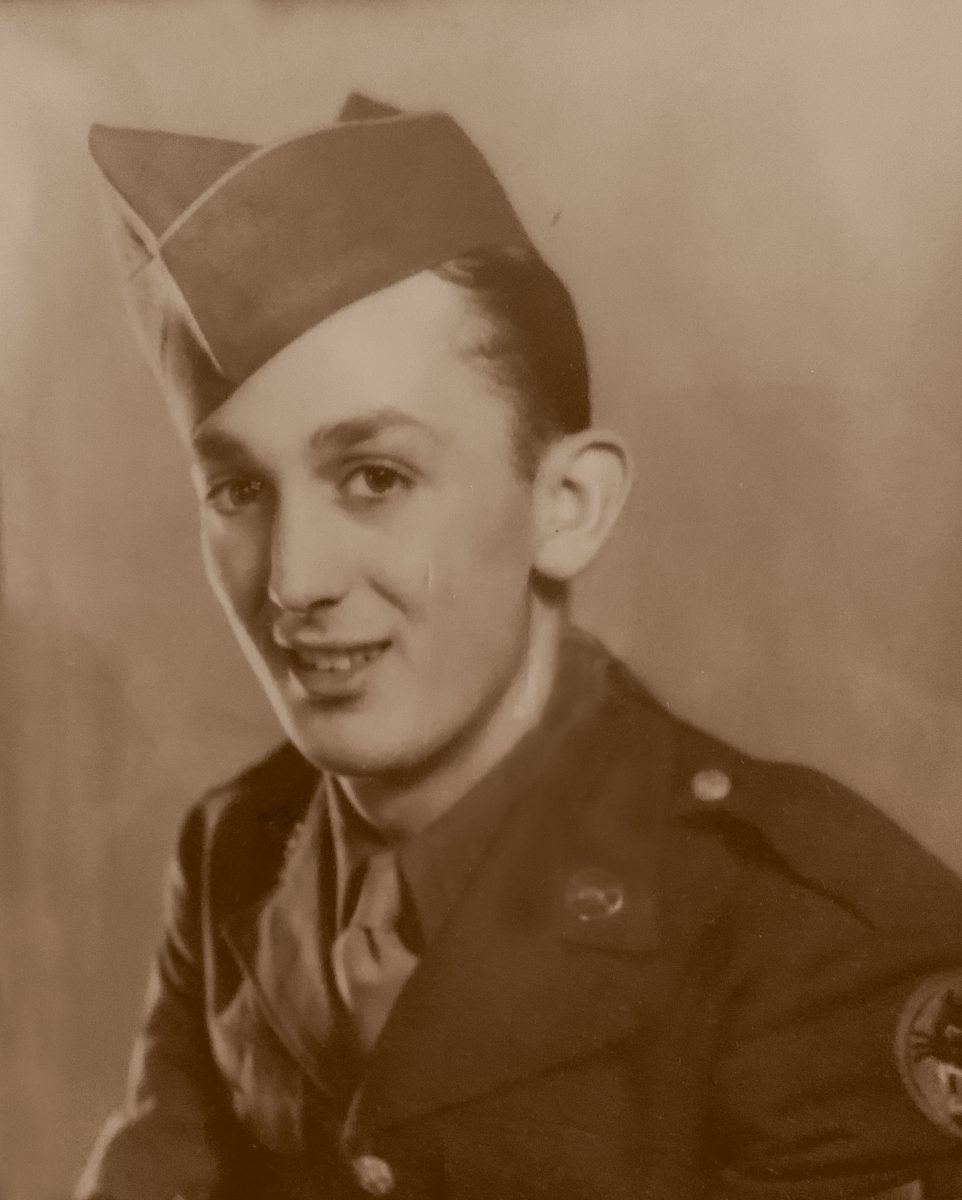

“The war changed my whole life,” James Pasanello, 94, of Hastings-on-Hudson, New York, told LifeZette this week in a series of exclusive interviews.

Drafted into the Army in March 1943 at age 18, Pasanello became a highly trained radio operator — he already knew Morse code when he entered the service, courtesy of his years as a Boy Scout in New York. As a result of his skills, his instincts, and divine providence, he dodged death in the European theater a number of times.

Late on the evening of Dec. 24, 1944, for example, troops from his division boarded the SS Leopoldville in Ashchurch, England. They were bound for Cherbourg, France, to fight in the Battle of the Bulge. The ship carried more than 2,000 American soldiers.

Pasanello was supposed to be on that ship along with other men in his convoy — but he and a group of soldiers had peeled off to try to locate a Catholic church that night.

Why? It was Christmas Eve — and they wanted to attend Mass.

“I have been asked many times in my life, ‘How come you go to church all the time?'” he said. “I always told people, ‘Some day I will tell you.’ Well, now you know.”

Ernest Childers, a Native-American soldier and Pasanello’s boss at the time, was among the group who went to Mass that night, though he wasn’t a Catholic. Childers later won the Medal of Honor for his heroic actions in military combat.

“We had a hell of a time trying to find a Catholic church that night,” said Pasanello.

They finally found one at around 11:30 p.m.

He later learned the Germans had sunk the SS Leopoldville when it was a mere 5.5 miles off the coast of Cherbourg. More than 760 soldiers either died in the blast or perished in the cold waters off the shore of France in that tragedy.

The Christmas Eve sinking was among the worst in U.S. history — but most Americans didn’t know about it at the time or even for years afterward.

“Military censors concealed the sinking of the SS Leopoldville to the American home front so that morale wouldn’t be broken and to keep the Axis from knowing that so many soldiers for the war would never make it,” as the website of the National World War II Museum in New Orleans explained it.

On December 26, Pasanello and his convoy boarded a different troop ship bound for Cherbourg, and “we were five miles out at sea when we saw bodies floating in the water, not realizing they were men from our outfit. While ships were picking up the bodies, we continued to Le Havre. We docked and got off the ship and saw body bags piled up like stacks of wood.”

When recounting this story in his typical forthright style, Pasanello paused for a moment. “I’m very glad we went to church on Christmas Eve,” he said.

He was later assigned to the highly fortified French city of St. Nazaire. “The submarine pens under the city were in full operation,” he said, and shared with LifeZette a five-page memoir he wrote that recounts his military service, including his time in St. Nazaire. “They [the Germans] sunk many ships, then ran back under the city for protection,” he said.

He conducted numerous patrols and had to monitor the airwaves — and even after Germany surrendered in May 1945, Pasanello remained in the Army. After service in Linz, Austria, he was finally sent home in 1946.

“It sure felt good to see the Statue of Liberty” again when he sailed back to New York, he noted. He had said a prayer on his way to war, when he first passed the statue, asking God to keep him safe and return him home to the United States when his military service was over.

“No more wars — that’s what I wish for. That’s what I want to hear today.”

“If you have faith, and believe, you got it all,” he said this week. “God bless America.”

Safely back in the lower Hudson Valley, he got married and raised a family — two sons and a daughter — and labored as a building machine operator for the railroad. He spent most of his working years in construction in New York City.

He has been active in the VFW and American Legion in his town for many years and wishes more Americans today appreciated the sacrifice of servicemen and servicewomen for our country.

“No more wars — that’s what I wish for. That’s what I want to hear today,” he said.

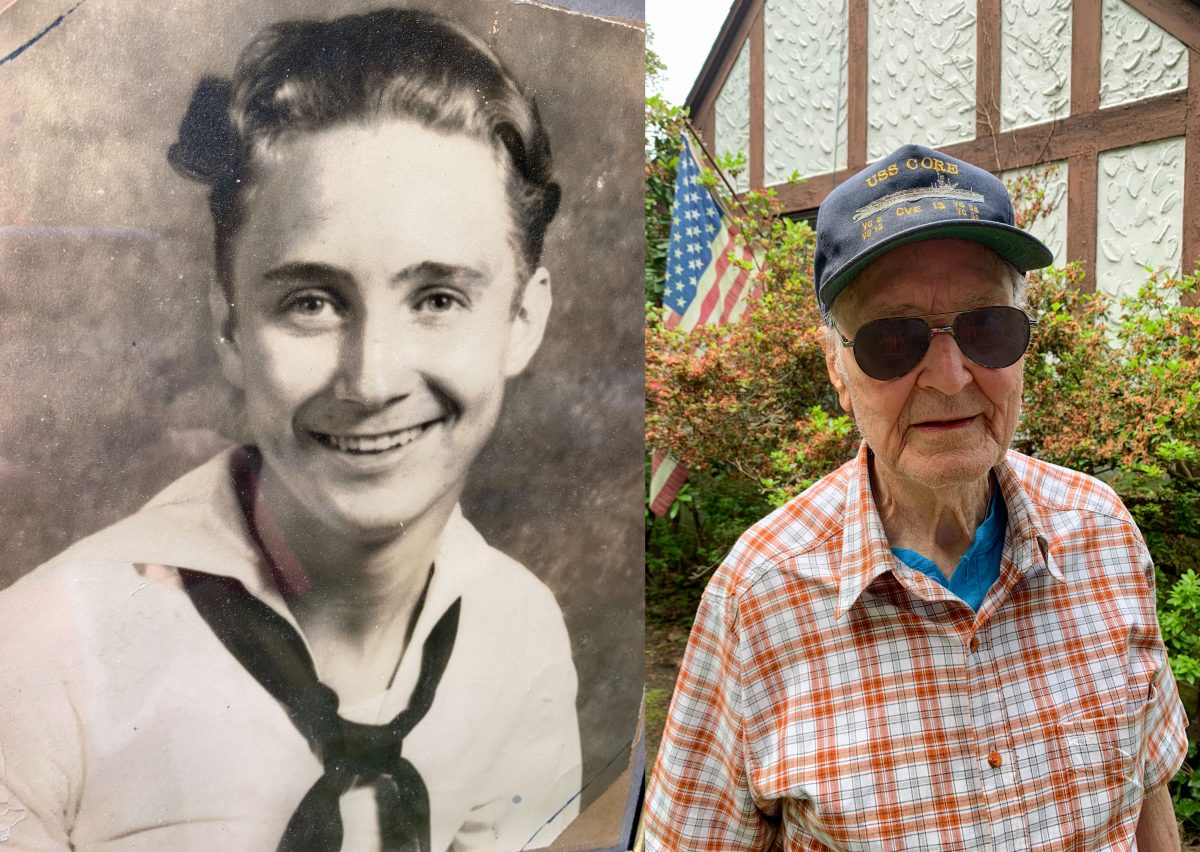

Edwin R. Paynter, 93, also of Hastings-on-Hudson, New York, served in the United States Navy during World War II.

He was in combat for 22 months, in both the Atlantic and the Pacific.

Paynter grew up in Queens, New York, and entered the service when he was 17. He served for a total of two-and-a-half years.

On D-Day, he was in port in Norfolk, Virginia.

“I was stationed on a ship — an aircraft carrier — which had torpedo bombers and fighter planes,” he told LifeZette this week. “We went out into the Atlantic and looked for submarines. We sank them,” he added.

“When you talk about D-Day, I was not involved personally, but we would go out to sea for two months or more at a time without seeing any land, trying to get submarines.”

His two brothers also served in World War II. “My mother had three sons all in combat at the same time. She was a nervous wreck,” he said.

He said his mom was about 110 pounds and “donated I don’t know how many pints of blood” for American servicemen during the war years.

His father worked in the Brooklyn Navy Yard and his sister worked on the war effort as well.

“So we were all involved,” he said, hitting on a key difference in the nation and its mood back then — and the way things are today. “Everybody from the Boy Scouts to so many other people” took part in the war effort, he said.

Any American who was alive at that time basically played a role in one way or another in pro-American activities. “It wasn’t like the other wars where [our men] fought overseas and nobody really knew about it.”

He sailed into Pearl Harbor — and was in Japan the day the country surrendered.

“We picked up Japanese aircraft and brought them back to the United States,” he said.

After World War II, his ship became a supply ship. It was used in both the Korean War and in Vietnam, he said.

Paynter got out of the service in 1946 and became a New York City firefighter. He worked in Brooklyn, Manhattan, and the Bronx for a total of 37 years.

Like Pasanello, he, too, has been active in veterans’ groups and today is most active in the American Legion.

Reflecting on the importance of D-Day and on America’s victory in World War II, Paynter spoke clearly and deliberately. “For servicemen like myself, you remember the guys who didn’t come back,” he said.

“Six men from my neighborhood in Queens — guys I knew personally — never returned.”

“We had to win that war,” he added. “Everybody was making sacrifices. Everybody was pitching in.”

He also said, “The World War II guys feel that they were there when the country needed them.”

And they were.

Don’t miss this video:

Join the Discussion

COMMENTS POLICY: We have no tolerance for messages of violence, racism, vulgarity, obscenity or other such discourteous behavior. Thank you for contributing to a respectful and useful online dialogue.